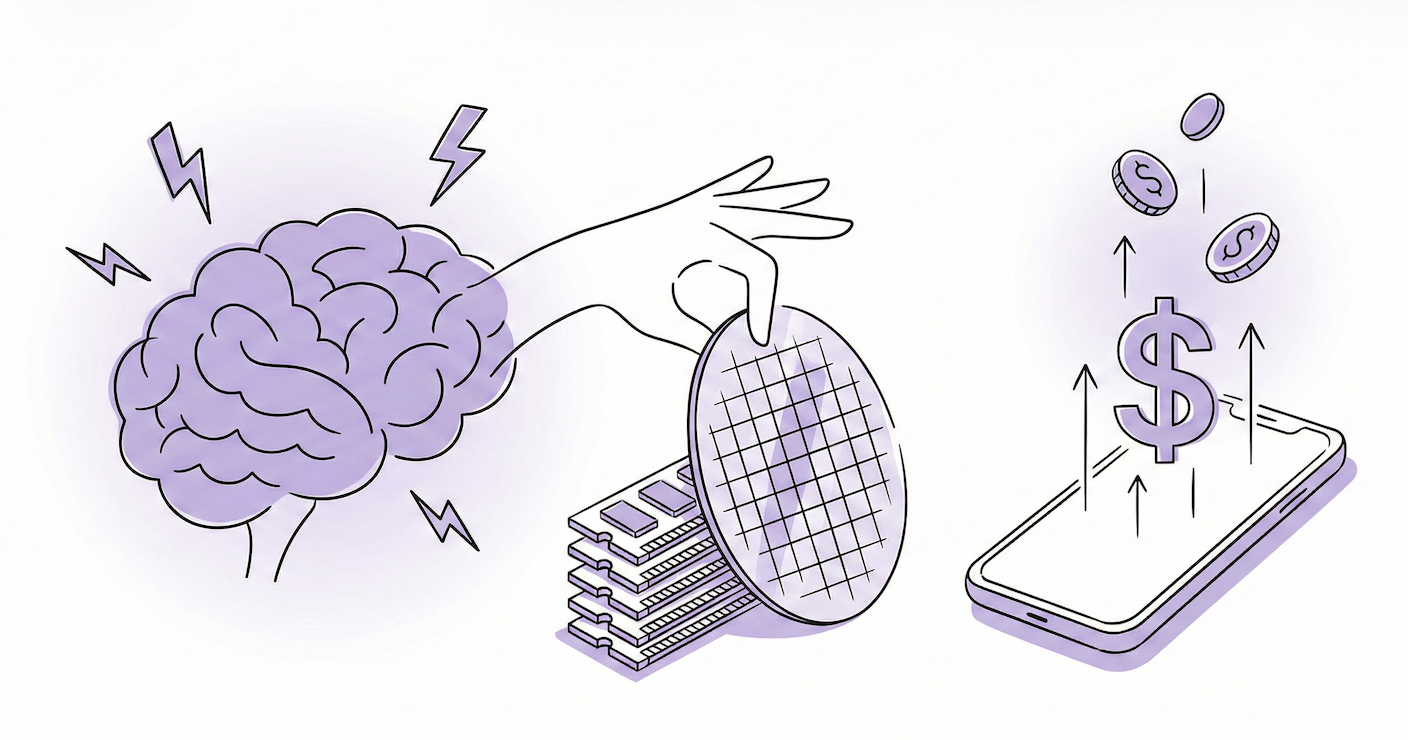

Darwin’s CEO Noam Maital explores how AI’s massive appetite for DRAM is monopolizing global supply and diverting critical silicon away from traditional consumer electronics. This structural shift is set to drive up costs for smartphones and laptops as the rising price of semiconductor "intelligence" eventually hits the consumer’s wallet.

In September of last year, OpenAI quietly locked in close to 900,000 DRAM wafers, a volume so large it represents roughly 40 percent of global monthly production, and that single number should fundamentally change how we think about the AI moment we are living through. This is not a story about prompts or model releases or viral demos. It is a story about factories, long-term supply contracts, and a finite amount of ultra-purified silicon being redirected at unprecedented scale toward a small number of AI platforms. While the public conversation remains enchanted by what generative AI can do, the real action is happening far from the spotlight, inside fabs in South Korea and Taiwan, where decisions made today will quietly shape prices, availability, and trade-offs across the global economy for years to come.

To understand why this matters, you have to understand what DRAM actually is. Dynamic Random Access Memory is not storage, and it is not optional. It is the short-term working memory of every modern computing system, the place where data lives while it is actively being processed. On a smartphone, DRAM is what lets you switch between apps without lag. On a laptop, it is the difference between a smooth day of work and a spinning wheel of death. In large language models, DRAM is even more critical. Every word predicted, every intermediate calculation, every layer of reasoning briefly lives in memory before disappearing. Intelligence at scale is impossible without massive, fast, and reliable DRAM.

The scale at which AI systems consume this memory is unlike anything the semiconductor industry was designed for. A single advanced AI accelerator today may rely on 80 gigabytes or more of high-bandwidth memory just to operate efficiently. Training or running a frontier model requires tens of thousands of these accelerators working in parallel. That translates into a demand profile that dwarfs traditional markets like PCs or smartphones. Global DRAM production in 2024 was roughly 2 million wafers per month. When one organization effectively reserves nearly half of that output, it is not a marginal shift. It is a structural one.

What makes this even more consequential is that these wafers are not flowing back into the general-purpose market. They are being tightly integrated into custom AI systems, optimized for specific workloads, and effectively removed from circulation. This is not a temporary spike that resolves itself in a quarter or two. It is a long-term reallocation of capacity away from consumer electronics, industrial systems, and automotive platforms and toward AI infrastructure that views compute as existential. When demand becomes this concentrated, prices stop being set by average buyers and start being set by whoever is willing to pay whatever it takes to avoid slowing down.

That dynamic has downstream consequences that extend far beyond AI labs. When hyperscale buyers are comfortable paying double or triple historical prices to secure memory supply, everyone else gets pushed down the priority list. Manufacturers building phones, appliances, medical devices, and vehicles suddenly face longer lead times and higher component costs. Design cycles stretch. Margins compress. Some products get delayed. Others quietly get more expensive. This is how a procurement decision made to support a new AI model eventually shows up in the price tag of a device sitting on a retail shelf.

For everyday consumers, this all sounds abstract until it is not. Over the next few years, the impact will be subtle but persistent. Smartphones will get more expensive not because screens or cameras suddenly cost more, but because the memory inside them does. Laptops will see fewer aggressive discounts. Cars, already packed with electronics, will quietly absorb higher semiconductor costs into their sticker prices. Even household appliances, now increasingly computerized, will reflect the rising floor of compute costs. If the price of intelligence keeps rising at the silicon level, how long before we start feeling it everywhere else?